Modernize or Maintain – What is the Best Way to Improve the Endangered Species Act?

Bald eagle, Florida manatee, and American alligator populations rebounded under the protection of the Endangered Species Act. Photo credit: USFWS.

By Orion McCarthy

The Endangered Species Act, the landmark U.S. law for protecting imperiled species, has enabled the recovery of iconic species such as the bald eagle, American alligator, and Florida manatee. While lauded by some as the most successful environmental law in U.S. history, the Act faces threats of extinction from Congress, which views the law and other conservation programs with increased suspicion and hostility.

Since 1996, there have been more than 300 direct challenges to the Endangered Species Act, the majority of which have occurred in the past five years. Members of Congress routinely introduce bills to eliminate protections for specific species or alter major provisions of the Act. While most have failed to pass, the increasing frequency of these attempts has alarmed scientists and environmentalists alike.

Supporters of the Endangered Species Act deride these challenges as thinly veiled attacks on the law’s strong environmental protections. Opponents claim that the law, passed during the administration of President Nixon in 1973, is no longer effective and should be “modernized.”

Given the rising frequency of congressional challenges to the Endangered Species Act, it is worth examining what modernizing the Endangered Species Act would entail. What are the underlying forces behind lawmakers’ calls to modernize the Act? What do lawmakers wish to change most about the law, and who stands to benefit from those changes? Could a revamp of the law benefit endangered species, or would changes likely come at their expense in favor of other groups?

One overarching question must be addressed before the above questions can be answered: does the Act successfully protect imperiled species and facilitate their recovery?

How does the Endangered Species Act work?

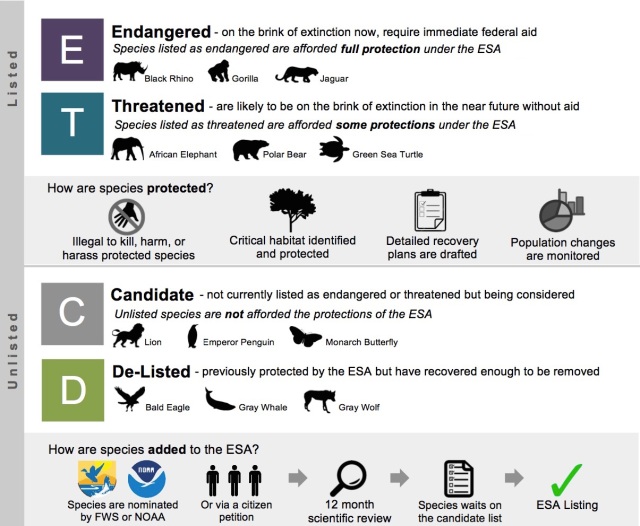

As a federal law, the Endangered Species Act is designed to protect species from harm and facilitate their recovery. Once a species is recognized as endangered under the Act, a process known as listing, that plant or animal is legally protected from human-caused harm or harassment, and critical habitat for the species is set aside by the federal government to be protected from development. Conservation strategies are outlined in species recovery plans, with the ultimate goal of removing species from federal protection once they have recovered. Approximately 2,325 species are listed as endangered or threatened under the Act.

Is the Endangered Species Act a success?

The Endangered Species Act has a mixed track record of success, which has allowed both its supporters and detractors to cherry-pick statistics to make their case. Supporters point to the low rate of species extinctions under the Act (less than 1% of listed species have gone extinct) as a sign of success, and argue that at least 227 species would have likely gone extinct since 1973 without Endangered Species Act protections. In addition, they tout the successful recovery and de-listing of 38 species under the Act, including the bald eagle, humpback whale, peregrine falcon, and stellar sea lion.

But with more than two thousand species listed under the Act, opponents of the law are quick to point to the rate of species recovery as a sign of the law’s ineffectiveness. Achieving only 38 recoveries when more than two thousand species are listed, they argue, is reason enough to modernize the Act. Critics also highlight the concerns of landowners and developers, who may be negatively impacted by the Act’s stringent requirements to protect critical habitat.

Highlighting the fact that less than 3% of listed species have fully recovered under the Act, Sen. James Inhofe (R-Oklahoma) remarked that “as a doctor, if I admit 100 patients to the hospital and only three recover enough to be discharged, I would deserve to lose my medical license.”

But Inhofe’s assessment neglects a key reality of conservation: species recoveries take time. No amount of modernization will reverse decades of habitat degradation, exploitation, and population decline overnight. While the average recovery time specified in Endangered Species Act recovery plans is 63 years, the average species has only been listed under the Act for 36 years. For these species, full recovery and delisting is not a reasonable metric for success.

Instead, conservation efforts for recently listed species should be judged based on progress towards recovery targets. A 2012 analysis of the Endangered Species Act found that 90% of listed species are recovering at or above the rates outlined in their recovery plans, which suggests that these conservation efforts are succeeding.

In addition, the recovery of a record-setting 29 species during the Obama Administration suggests that the rate of species recoveries is accelerating as the average duration of species listings increases.

While many species are showing promising signs of recovery under the Act, there is certainly room for improvement. Although the Endangered Species Act is highly successful at protecting species from simple threats, it is less effective at addressing complex ones. For example, the Endangered Species Act led to the recovery of the American alligator by restricting hunting, the primary threat facing the species. However, species like the Hawaiian monk seal, which face a combination of threats including marine debris, habitat loss, disease, and climate change, have been slower to recover.

Another drawback of the Endangered Species Act is that species listings become vulnerable to political processes. Species with a clear scientific need for conservation could be precluded from a listing under the Act by economic or social factors, or by political controversy. Prolonged battles over the greater sage-grouse, northern spotted owl, and other controversial species have pitted landowners and environmentalists against each other and made species conservation into an unnecessarily polarizing and partisan issue.

The process of listing the greater sage-grouse, a pheasant-like bird that lives in native prairie habitat in the Midwest, sparked special riders and legal battles over the listing’s implications for agriculture and oil and gas development. Photo credit: National Wildlife Federation.

Should the Endangered Species Act be modernized?

While the Endangered Species Act is arguably the most powerful and effective conservation law in the United States, it could certainly be improved. However, “modernizing” the Act under current political conditions would almost certainly weaken both the power and effectiveness of the statute and place imperiled species at a greater risk of extinction.

Through campaign promises and proposed bills, Republicans have articulated their intention to roll back environmental protections and return control of federal land to the states. The newly empowered Republican majority in Washington has already held multiple hearings this year to scrutinize the Endangered Species Act and discuss major changes to the law.

At a congressional hearing in January 2017, House Natural Resources Committee Chairman Rob Bishop (R-Utah) remarked that he “would love to invalidate” the Endangered Species Act and “prioritize people over ideology.” Rep. Tom McClintock (R-California), chairman of the House Subcommittee on Federal Lands, expressed a desire to amend the law to ease logging restrictions in national forests, while Rep. [Senator} John Barrasso asserted that modernizing the Act would “eliminate a lot of red tape and bureaucratic burdens” and “create jobs.”

Remarking on the repeated efforts to weaken the Act, endangered species policy specialist at the Center for Biological Diversity Jamie Pang said “one [proposed] bill would delist any species that did not cross state lines, and effectively transfer management of that species over to the state. If you take away federal protections and give them to hostile states, that’s the end of the species.”

President Donald Trump, for his part, has said that he is an “environmentalist” but that environmental regulations have gotten “out of control.” The president’s Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke was given a lifetime score of 4% by the League of Conservation Voters during his time in Congress. In addition, Trump’s FY18 budget proposal would cut funding to the two agencies tasked with implementing the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, by 12% and 16% respectively.

Even as Republicans target the Endangered Species Act, voters continue to support the Act in its current form. A 2015 poll from strategic consulting firm Tulchin Research found that 90% of voters back the law, with support extending across all demographic groups. The poll also found strong support for the notion that federal scientists, not members of Congress, should make decisions about which species to protect under the Act.

Increasing the role of science in decisions about endangered species listings is one way the Endangered Species Act could be improved. Conservation groups have suggested several other improvements to make the Act more effective, including:

- Embracing adaptive management of endangered populations using a diverse range of conservation tools, in addition to habitat conservation;

- Normalizing the process for designating critical habitat for listed species;

- Encouraging landowner involvement in endangered species recovery programs where possible;

- Improving collaboration between federal and state governments;

- Streamlining the listing process to more closely resemble the process of scientific peer review; and

- Ensuring that federal agencies tasked with implementing the Act are adequately funded.

Unfortunately for endangered species, securing these changes in the current political climate is extremely unlikely. Politicians who are ideologically opposed to science and environmental protection would sooner weaken the Endangered Species Act than improve it. Until political winds substantially shift, the best course of action for wildlife is to preserve the Endangered Species Act in its current form.

To read more about the ESA and other pressing environmental concerns, visit Orion McCarthy’s conservation blog at howtoconserve.org]]>