Report of RNRF Round Table: Sustainably Managing California’s Groundwater in the Midst of a Prolonged Drought

Ellen Hanak, vice president of the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) and director of the PPIC Water Policy Center, spoke at a virtual meeting of the Washington Round Table on Public Policy on June 9, 2021. Her talk was titled, “Sustainably Managing California’s Groundwater in the Midst of a Prolonged Drought.”

Background

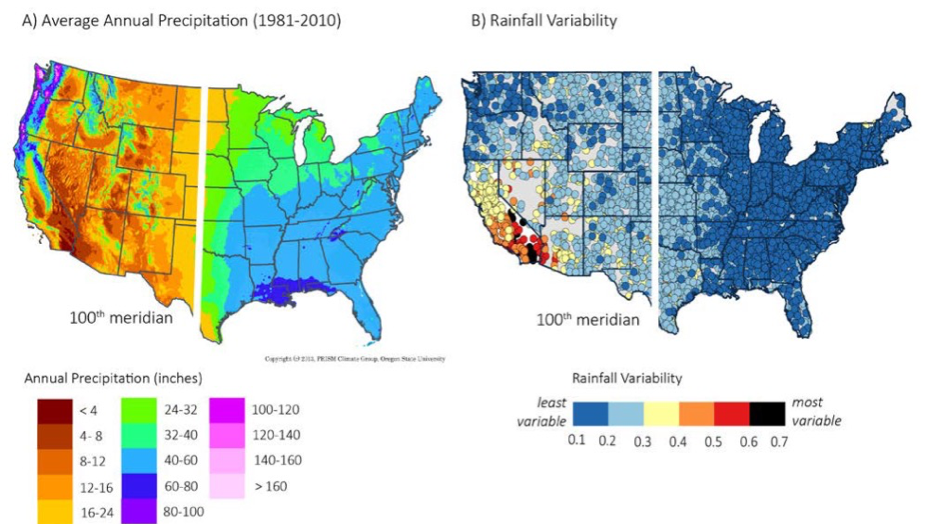

The Western region of the United States, west of the 100th meridian, has a drier and more variable climate than the East, as shown in Figure 1. Both of these characteristics are becoming more pronounced as the climate changes, leading to new challenges in water management. California’s climate is extremely variable, and while droughts have always been a recurring feature, climate change is making them more common and more severe compared to historical conditions. Warmer temperatures also make drought management more complex due to increased evaporation, lower soil moisture, and higher water temperatures—which stress many fish species and cause water quality problems (Mount et al. 2018).

Figure 1: Precipitation in the West is Lower and More Variable

Water management in most Western states has historically been conducted under the assumption that every summer will bring dry weather. California is no exception. Home to the largest agricultural sector in the nation, it has always needed irrigation to grow its crops during the summer months. Water is stored in both surface and undergroundreservoirs for use during summers, as well as in dry years. Stored surface water tends to be used early in droughts, so groundwater proves very valuable as a reserve in multi-year droughts. Hanak explained that it is fine to rely on groundwater during dry years as long as this is done in a sustainable way. In some parts of the state, this has not been the case – even in non-drought years, some areas have either continued to deplete reservoirs or not replenished them sufficiently to maintain stable storage levels in the long-term. This has led to a chronic, serious overdraft problem in some areas.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act

During the last drought, which lasted from 2012 to 2016, this overdraft problem led to the passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) in 2014. Hanak said that this act was “100 years in the making” – California’s modern water code for surface water was enacted in 1913 and went into effect in 1914. 100 years later, the state enacted comprehensive groundwater legislation. It was the last Western state to implement a statewide groundwater management system.

While SGMA is a state law, it is primarily implemented by local agencies and jurisdictions. Under the act, local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies are formed to manage groundwater and develop and implement Groundwater Sustainability Plans. To ensure that local jurisdictions do this, state agencies can take control over groundwater management in a basin if the act is not being satisfactorily implemented there. Thus far, this motivating factor has been successful. Implementation has been proceeding and jurisdictions are seeking to comply with the new law.

There are about 85 priority basins that have to develop these sustainability plans. They are mostly in agricultural areas, where there is less pressure to sustainably manage groundwater compared to urban areas. (In many urban areas that rely on groundwater—both in Southern California and Silicon Valley—more intensive local groundwater oversight has been in place for decades.) Deadlines for the development of groundwater sustainability plans are either in 2020 or 2022 depending on how serious the overdraft of groundwater is in the basin. Critically overdrafted basins, which had to submit their plans in 2020, are largely located within the San Joaquin Valley, plus some parts of the Central Coast. After submitting their plan, agencies have 20 years of implementation to achieve groundwater sustainability, but they must also avoid significantly unreasonable, undesirable effects of pumping in the interim. Plans must be updated every five years and include data on the status of their implementation. These are early days in SGMA implementation, but the law is already shifting how water is managed in California.

The San Joaquin Valley

The San Joaquin Valley is the largest agricultural region in California and “ground zero” for the implementation of the SGMA (Hanak et al. 2019). Hanak said that if you eat fruits and nuts in the US, and even some brands of wine, they likely came from the San Joaquin Valley. While it is a booming agricultural region, it is very dry and relies heavily on bringing surface water in from the northern part of the state, as well as pumping groundwater. There is a large imbalance between supply and demand for water in this region – on average, there is a groundwater overdraft of about 2 million acre-feet per year, accounting for about 11% of net water use in the region. This is causing chronic depletion of groundwater basins that took millennia to fill.

During the last drought, California experienced the consequences of this depletion: dry wells, sinking lands, and reduced groundwater reserves available for use during future droughts. The wells that have gone dry include those used for agriculture but more commonly they are shallow drinking water wells used by residences, an important consideration from an equity perspective. Sinking land is harmful to urban infrastructure but can also be a problem in rural areas, causing damage to roads, bridges, and major water conveyance infrastructure.

Hanak explained that the issue comes down to a simple math problem: attaining balance and sustainability for groundwater either means increasing water supply from other sources, decreasing water use, or (most likely) a combination of both. There is an important economic component to this problem as well. Some solutions are more costly than others; in particular, some methods of supply augmentation like ocean desalinization are very expensive. Ultimately, agriculture is a business, so supply must be managed in a way that is cost effective.

More than 90% of net water use in the San Joaquin Valley is for crop irrigation. For this reason, agriculture is the sector that will require the most adaptation to achieve sustainability. Inflexible cuts to local water use are not preferable because they tend to cause the largest crop revenue losses, diminished farm-related GDP and job losses, and land fallowing. Water trading (both locally within basins and valley-wide) allows water to move to the most productive lands; this could reduce the costs of adjustment by more than 60%. There is also some scope for augmenting supplies cost-effectively, such as through groundwater recharge, which is a process of actively storing water in the ground. Different parts of this region have varied access to surface water, making cooperation very important.

Over-Reliance on Supply Management

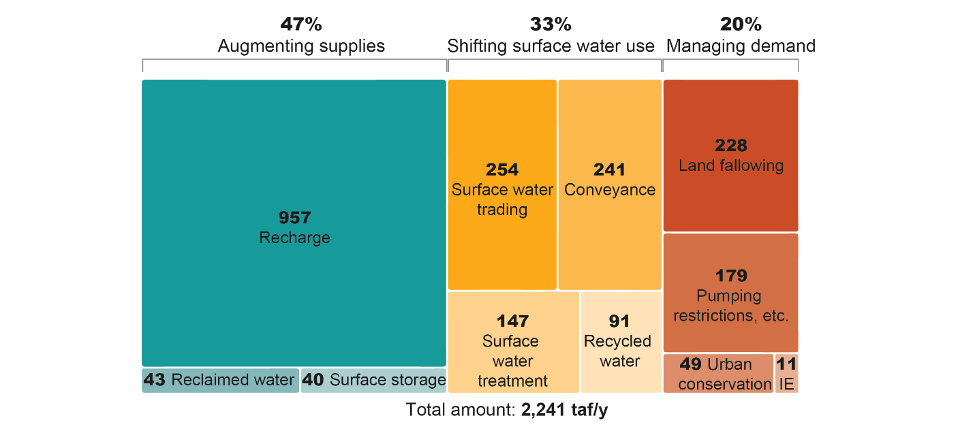

Hanak noted that the groundwater sustainability plans that have been submitted so far in the San Joaquin Valley largely do a good job of recognizing the problem of groundwater overdraft in their basin. Agencies had to submit plans for how they will address this problem through supply projects, demand projects, or a combination of both. In these first plans, 47% of the solutions submitted are based on augmenting supply, as shown in Figure 2. This is mainly done by capturing additional flood flows in wet years and recharging groundwater basins. A third of solutions involve shifting water use from one use to another, such as by treating surface water for residential use that was previously used for another purpose. While such solutions can augment the planning area’s supplies, they entail reductions in supplies used by other parties within the region—something not accounted for in the overall planning process.

Only 20% of current proposed solutions utilize demand-management solutions. Hanak said that this number needs to be much higher to achieve groundwater sustainability. There is a reason that demand-management plans are lagging behind where they need to be; demand management is a difficult conversation to have. Over the next twenty years, PPIC research estimates that between 500,000 and 750,000 acres of agricultural land will have to come out of production to achieve groundwater sustainability (Hanak et al. 2019 ). This is 10-15% of irrigated acreage in the region.

People are understandably worried about impacts on local communities and economies as water demand is managed. During the Q&A session, Hanak explained that concerns are not limited to job and revenue losses. Depending on how land is managed, fallowed land could cause increased dust in areas that already have air quality issues. Fallowed land can also create pest and weed problems for neighboring farms. Potential solutions include intermittent fallowing (for instance, only fallowing land in dry years), as well as using land for habitat recovery to benefit endangered species. Using former farmland for utility-scale solar power installations is also an option, but ensuring that this creates benefits for local economies is important. Hanak expressed confidence that as implementation of SGMA proceeds, people will devote increasing attention to implementing demand-management solutions.

Figure 2: Plans Emphasize Recharge, Have Limited Focus on Demand Management

Addressing the Negative Consequences of Groundwater Overdraft

While groundwater sustainability agencies have 20 years to achieve sustainability, they have to do so in a way that will avoid significant undesirable impacts of groundwater depletion. The law is very comprehensive in outlining these undesirable consequences and explicitly dictates that plans need to explain how they will be addressed. The undesirable consequences of groundwater overdraft include:

- Lowering groundwater levels

- Reduction of storage

- Land subsidence

- Seawater intrusion

- Surface water depletion

- Degraded water quality

Options include limiting pumping enough to avoid these problems, or mitigating the effects, for instance by providing alternative water supplies to those whose wells are adversely affected. Mitigation is not always a viable option; some issues can only be addressed by prevention. This could require some basins to attain groundwater sustainability before the end of the 20-year SGMA window.

PPIC reviewed how plans address two of these impacts that are particularly salient in the San Joaquin Valley: the lowering of groundwater levels (which has major implications for shallow drinking water wells) and land subsidence.

Lowering Groundwater Levels

The most immediate impact that arises from lowering groundwater levels is to shallow drinking water wells, which are common in many rural areas. During the last drought, an estimated 2,600 domestic wells went dry, and roughly 150 small community water systems were at risk of shortages. This was one of the major reasons that the SGMA was passed. Some groundwater sustainability plans submitted thus far intend to maintain sufficient water level thresholds to prevent wells from going dry, and some have mitigation plans to drill wells deeper. But plans in some of the areas that experienced the greatest impacts in the last drought have no program to prevent or mitigate dry wells—a considerable planning gap.

Land Subsidence

Many San Joaquin Valley plans also allow for significant land subsidence to continue—in some cases by as much as 10-15 feet over the next 20 years. This is already causing infrastructure damage, including to major water conveyance infrastructure like the California Aqueduct and the Friant-Kern Canal. Subsidence can also cause compaction of the aquifer system that leads to a permanent reduction of groundwater capacity. This phenomenon was also observed during the previous drought. Hanak noted that these basins will probably have to reevaluate how they are addressing land subsidence.

Avoiding Impacts to Surface Water and Ecosystems

One important innovation of the SGMA is that it formally connects groundwater and surface water law. This creates more of an implementation challenge for less overdrafted basins (those that are not “critically overdrafted,” largely in the northern region of the state) because they are more likely to be in an area where groundwater is still closelyconnected to river flow. This means that these basins have to be more careful not to pump too much groundwater during droughts, since pumping can quickly reduce streamflow. This can have ecosystem impacts, including on endangered salmon and steelhead populations in Northern California.

The Current Drought & Short-Term Priorities

California presently is in the second year of another severe drought, the first since the one that prompted the California legislature to pass the SGMA in 2014. Water scarcity makes the supply-demand balancing act much more difficult. Drinking water impacts for rural communities are expected to escalate as more farmers turn to groundwater for irrigation.

The transition to sustainable management of groundwater in California is a long process, but to get off to a strong start and take into account the added challenges of ongoing drought, Hanak closed her presentation by identifying some priorities for the short-term:

- Address undesirable impacts of groundwater overdraft (including dry rural wells, ecosystem impacts in places with strong surface water-groundwater connections, and land subsidence).

- Develop strong water accounting frameworks and allocating pumping budgets. This incentivizes careful utilization of the resource, including trading and saving water.

- Assess smart infrastructure investments. This includes identifying where it makes sense to build new conveyance infrastructure to enable more recharge, expand trading, and allow for the use of surface water reservoirs alongside groundwater.

- Launch broad-based planning for both water and land. This includes finding the least harmful and most beneficial ways to take land out of agricultural production.

- Pilot innovative approaches to water trading, groundwater recharge, and land stewardship.

Hanak concluded by noting that efficient, equitable solutions to the multi-faceted challenges of managing groundwater will require increased cooperation among multiple parties, both within and across basins. And while this process is fundamentally one that requires local leadership, the state and federal governments can help with financial and regulatory incentives.

– Stephen Yaeger, RNRF Program Manager

The PowerPoint presentation Hanak used during the round table can be viewed here.

In her presentation, Hanak referenced a list of studies and reports for further reading on this topic. They include the following:

“Droughts in California” (fact sheet, April 2021)

“California’s Latest Drought in 4 Charts” (PPIC blog, May 2021)

“A Review of Groundwater Sustainability Plans in the San Joaquin Valley” (blogseries and public comments submitted to DWR May 2020)

“Water and the Future of the SJ Valley” (report, Feb 2019)

“Managing Drought in a Changing Climate” (report, Sept. 2018)

“Replenishing Groundwater in the SJ Valley” (report, April 2018)